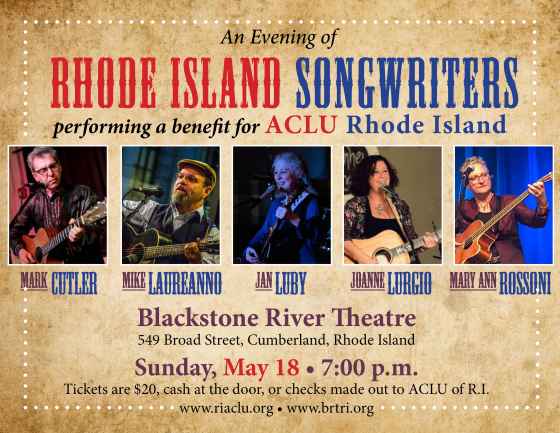

While almost nobody was looking, the Office of the Attorney General (AG) has abruptly made secret literally tens of thousands of government records. It happened in the context of a dispute over the release of one of the most innocuous documents one could imagine: a memo seeking the purchase of ceremonial lapel pins for members of the Attorney General’s staff. Yet this dispute’s ramifications for open government are nothing short of monumental.

For years, open government groups have complained that the Office of the Attorney General – the agency responsible for overseeing and enforcing the Access to Public Records Act (APRA) – has more often been a hindrance than a help to open records requesters, and has repeatedly undermined APRA through its actions and advisory opinions. In confirmation of this concern, that office may have reached a nadir with its filing last week of a short legal memo in response to former Rep. Patricia Morgan’s continued efforts to obtain records regarding the Attorney General’s expenditure of funds received from the so-called “Google settlement.”

The AG’s argument in opposition to release of the “lapel pin memo” not only tortures the reading of one of APRA’s exemptions to suddenly make unavailable to the public an enormously wide swath of important government documents, it also justifies denying people access to records based solely on the quantity of records their request seeks. Both of these positions do great damage to APRA and to the public’s right to know. What is cause for even greater alarm is that they have emanated from the office responsible for enforcing APRA.

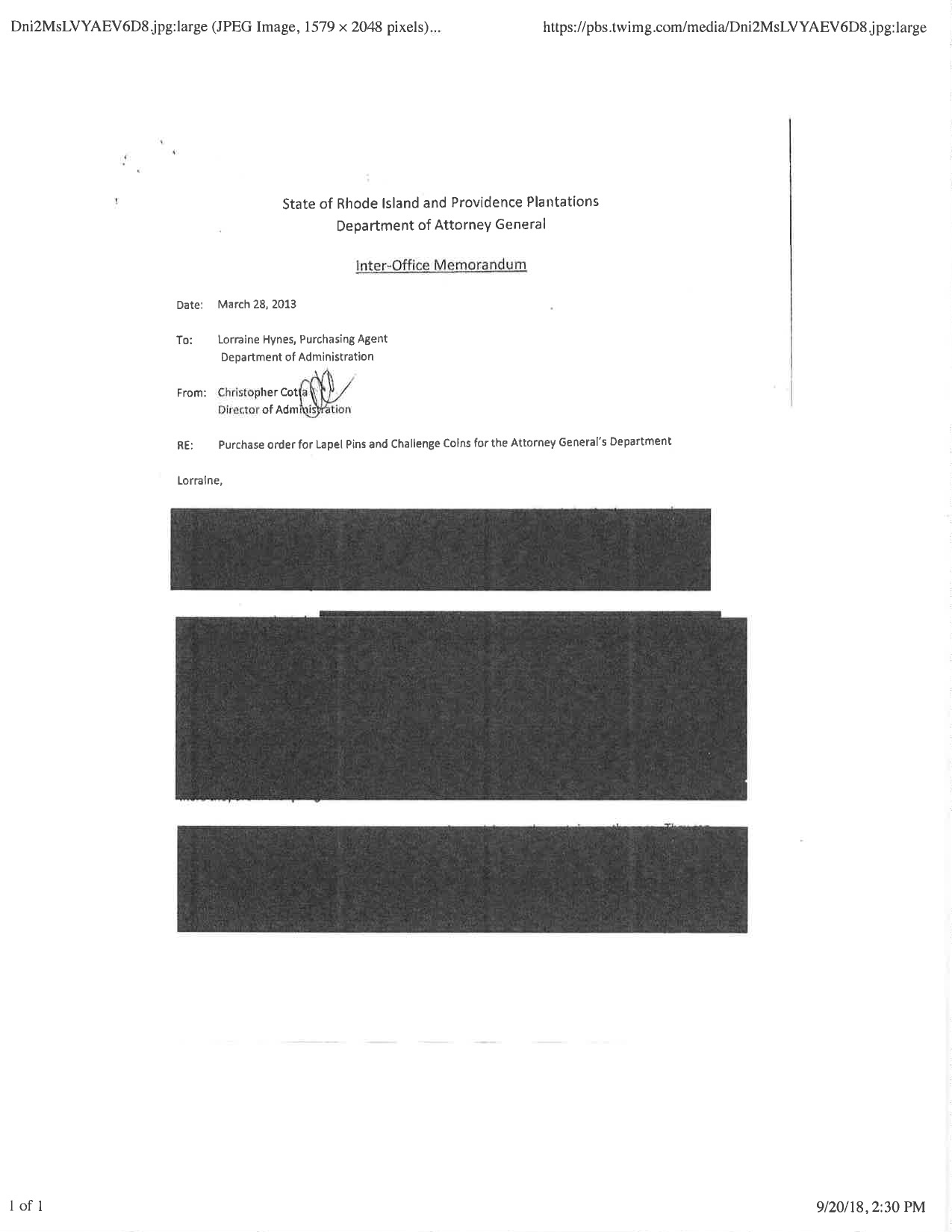

When the first set of Google records was released by the AG to Morgan some months ago, the ACLU was struck by the vast number of questionable redactions to the documents. Nothing exemplified this more than one particular document that was (sort of) provided to her: an inter-office memo from the Department of the Attorney General to the Department of Administration’s purchasing agent, regarding a “Purchase order for Lapel Pins and Challenge Coins for the Attorney General’s Department.” Except for the heading, the entire content of the document was redacted.

In court papers filed in October 2018, the AG justified redaction of that document by citing APRA’s Exemption K, which allows for the non-disclosure of “[p]reliminary drafts, notes, impressions, memoranda, working papers, and work products…” Because the document regarding the purchase of lapel pins “follows the format that one may expect of a ‘memoranda’ and is consistent with the plain language definition of a ‘memoranda,’” the AG argued, the document was completely exempt from public disclosure.*

However, the clear intent of  this exemption is to address unfinished business documents. Every other document cited in it – drafts, notes, impressions, and working papers – follows from the initial key word “preliminary,” and contains an element of incompleteness or tentativeness. Read in that context, the inclusion of “memoranda” makes sense, but to interpret it as making secret any document of a public body that is labeled a “memorandum” defies common sense and opens a gaping and completely unjustifiable loophole in APRA.

this exemption is to address unfinished business documents. Every other document cited in it – drafts, notes, impressions, and working papers – follows from the initial key word “preliminary,” and contains an element of incompleteness or tentativeness. Read in that context, the inclusion of “memoranda” makes sense, but to interpret it as making secret any document of a public body that is labeled a “memorandum” defies common sense and opens a gaping and completely unjustifiable loophole in APRA.

Unfortunately, at an October hearing on former Rep. Morgan’s objection to the wholesale redaction of thousands of pages of documents concerning the Google settlement, the Superior Court sided with the AG on all the redactions he made, without specifically addressing this reasoning.

Eager to determine whether there might be some other basis for redacting this harmlessly-titled document, the ACLU filed an APRA request with the Department of Administration (DOA), the recipient of the mysterious memo, for a copy of it. Surprisingly and disturbingly, the DOA said they could not provide the document – not because it was exempt from disclosure but because they physically were unable to find it without the invoice or purchase order number. Yet in the Morgan case, the AG had taken the position – also opposed by the ACLU – that, for “security” reasons, all invoice and purchase numbers had to be redacted. This left the ACLU in a true Catch-22 position.The ACLU therefore filed the same open records request with the Attorney General. Unlike the response to Rep. Morgan, the AG provided the ACLU a complete, unredacted copy of the lapel pin memorandum and invoice. As it turns out, the text of the memo is true to its title, and as boring a government document as the title suggested. So had the AG made an unintentional mistake in redacting the document given to Morgan?

In a word, no. In papers the ACLU filed with the Court last week, we pointed out that the release of the memo in response to our APRA request demonstrated that there had been no basis for the AG to withhold it from Morgan in the first place. However, the AG quickly responded by defending its decision and reaffirming that any government document meeting the definition of a “memorandum,” including this one, is exempt from disclosure under APRA.

In short, the AG has formally taken the legal position – and a court, regrettably, seemingly rubber-stamped it – that every state and municipal agency can withhold from the public any document that can be considered a “memorandum,” even though these records undoubtedly address and encapsulate key elements of public decision-making. Even worse, this is not just the last word of a departing Attorney General whose record on open government issues was, as a Providence Journal editorial recently put it, “dismal.” Instead, this most recent brief was filed under Attorney General Peter Neronha's name in the first week of his new position and who, when recently asked about the open records law, said “when in doubt, turn it over.”

As for why the ACLU got an unredacted copy, Attorney General Neronha’s office justified the disparate responses by stating that we had filed a “much more narrowly focused APRA request,” and that APRA gives public agencies discretion to release documents that are otherwise exempt from disclosure. That latter proposition is true, but that is very different from saying that APRA allows an agency to withhold allegedly exempt documents from some requesters while providing them to others. In fact, time and again the Attorney General has issued advisory opinions emphasizing that under APRA, no individual has any “greater interest in gaining access to a record than any member of the general public,” and that if a record is granted to one person, “the same records are available to anyone upon request.” West Broadway Associates v. Portsmouth Police Department, PR 14-26.

While the ACLU is pleased to have received this innocuously bureaucratic document uncensored, it is one that should never have been kept confidential in the first place. The notion that anything that can be labeled or considered to be a “memorandum” is now off-limits as a public record is astonishing. To our knowledge, no other government agency has ever tried to make this argument, but the state’s enforcer of the open records law has now shamelessly made it for them.

APRA declares the public’s right to access to public records to be “of the utmost importance in a free society.” The Attorney General’s alarming interpretation of a law meant to uphold a crucial principle of open government will cause great harm if left unchallenged. Both the General Assembly and the courts need to step forward and not allow this unjustifiable position to stand.

_____

* So as to leave no doubt about the breadth of his position, the AG’s court filing referenced definitions of the term “memorandum” to include “a brief record of an event or analysis of a situation, made for one’s own future reference or to inform others, and sometimes embodying an instruction or recommendation” and “a short document recording the terms of an agreement.”